The Australian school information website My School was launched in January 2010. In the initial press release of the website, the Chair of the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, which runs the site, stated

We expect the data will benefit parents, schools, governments and the wider community to better understand school performance.

Now, with more than 10 years of data what can we say about school performance? In this blog post I want to share some of the understandings that emerge from my analysis of My School data about remote First Nations education. These understandings would have been very difficult to make without the information provided on the site.

The value of My School to researchers like me

My School has been criticised for its inability to improve performance, its inability to show the quality of teaching, and the use of NAPLAN scores as a vehicle for comparing schools. These are all valid criticisms, but as a researcher I look at My School differently. My School provides detailed information about almost every school in Australia. There is data on enrolments, teachers and school staff, school finances, attendance, NAPLAN performance, socio-educational advantage, school type, remoteness, year ranges, First Nations enrolments, gender, year 12 completion, and students speaking languages other than English.

Early on in the life of My School my colleagues and I, working in the Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation’s Remote Education Systems project, developed a simple database for capturing information about the approximately 290 very remote Australian schools. Every year I have added the latest data about very remote schools. I now have 11 years of data. The analysis of this data has yielded some astonishing findings, some of which I will briefly outline.

Here are five of my findings that may be of interest to you.

1. Disadvantage does not affect attendance rates for First Nations students

Using ICSEA data we have been able to show that within the group of very remote schools, the level of socio educational advantage makes almost no difference to attendance. Figure 1 maps school attendance rates against ICSEA scores for very remote schools with greater than 80 per cent First Nations students for the period 2008 to 2018. The R2 value of 0.0196 indicates an insignificant association between the two variables. The commonly held views about disadvantage is that as disadvantage increases, attendance rates should go down. But in this analysis this assumption does not hold true.

Figure 1. ICSEA score vs school attendance rate for Very Remote schools with >80% First Nations students (2008-2018)

2. Attendance makes very little difference to NAPLAN outcomes

As with disadvantage, the commonly held assumption is that low attendance causes ‘poor’ outcomes. Figure 2, based on My School data, shows that this logic is questionable. The R2 value of .1083 suggests that attendance explains about 10 per cent of the difference in NAPLAN scores (in this case Year 3 Numeracy).

Figure 2. NAPLAN score (Year 3 Numeracy) vs school attendance rate for Very Remote schools with >80% First Nations students (2008-2018)

3. Attendance strategies don’t work

Attendance strategies are intended to improve school attendance. Two federally funded programs, the School Enrolment and Attendance Measure (SEAM), and the Remote School Attendance Strategy (RSAS), have targeted schools with low attendance rates. SEAM, which begin in 2009, was abandoned at the end of 2017. Then Indigenous Affairs minister Scullion labelled it as a ‘badly designed and woefully implemented program’. According to the Minister, it was ‘ineffective in getting kids to school’.

My School data (Table 1, below) confirms this assessment, with attendance rates for SEAM schools down 9.2 per cent since the program began. My School shows us that the downward trend was evident by 2012. RSAS is also designed to improve attendance. However since it began in 2014, attendance rates in RSAS schools have dropped 6.0 per cent. Meanwhile schools without SEAM or RSAS have also reported a decline in attendance rates, down 3.7 per cent in the same period. RSAS continues to be funded, but like SEAM it appears to be ineffective.

It is worth asking why there is even a need for an attendance strategy when as we saw earlier, attendance makes so little difference to academic performance.

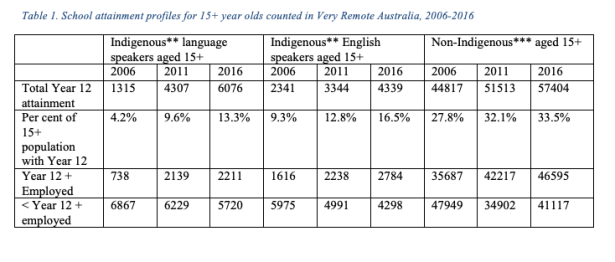

Table 1. Attendance rates for Very Remote schools with >80% First Nations students

4. Three things that DO make a positive difference

If attendance and disadvantage don’t make a difference what then does? My School gives us some important evidence. Figure 3 (below) summarises nine years of data, where school finances are reported. While we should be careful about not attributing causality, what we can say is that schools that have higher levels of funding per student, and schools with lower staff to student ratios, have higher attendance rates.

Interestingly, the biggest effect on attendance is not the teacher student ratio, but the non-teacher student ratio. In very remote schools with mostly First Nations students non-teaching staff are mostly local staff. They could be classroom assistants, administration workers, grounds staff or bus drivers—regardless, it seems they make a difference.

Figure 3. Relationship between attendance rate, student to staff ratios and recurrent income per student, Very Remote Schools with >80% First Nations students, 2009-2017

5. The failure of programmatic solutions

The One criticism of using My School for research purposes is that it does not tell us about individual students. However, when programs like RSAS are designed to lift school attendance, then it is reasonable to use school level data. One program that was designed to improve literacy in remote schools was the Literacy for Remote Primary School Program (LFRPSP) which was introduced as a trial in 2014 employing Direct Instruction (DI) and Explicit Direct Instruction methods. The trial received $30 million of public funding including extensions in 2017 and 2018 following an evaluation.

Did it work? My School tells us that it did not, and that based on the findings to 2017, an extension of the trial was not warranted. NAPLAN scores in DI schools fell by an average of 23 points while non-intervention school scores increased by 4 points.

Figure 4. Year 3 reading scores for Very Remote Direct Instruction (LFRPSP) and non-intervention schools, pre-intervention compared with post-intervention period

Summing Up

Are we any the wiser from 10 years of My School? From a research perspective the answer is an emphatic yes.

In Very Remote schools with First Nations students, My School has given us evidence we need to show what does and doesn’t make a difference to issues considered important for policy makers and advisers. What My School has shown us is that a focus on attendance in remote schools is ineffectual. It also tells us that deficit discourses of disadvantage are fundamentally flawed and what we are currently measuring as ‘advantage’ fails to explain the dynamics of success and achievement in remote schools. It also allows us to draw our own evidence based conclusions on whether programs are working or not.

My School data tells us that financial investment in remote schools works, particularly where it is directed at teachers and local support staff, and apart from any other benefits, that investment is reflected in higher levels of engagement and better academic performance.

With all the evidence, is anyone taking any notice?

The answer to this question is a qualified yes. There is increasing recognition that the deficit discourses of remote education are inappropriate and don’t reflect the lived reality of those who live there. It is also clear that stakeholders in remote education use this data and analysis for their own purposes. From personal experience I know that policy advisors in government departments seek out our analysis and are very interested in what it says. But how that translates into policy is unclear.

Beyond the evidence, government policy and programs are inherently political. Nevertheless, the value of My School as a data source is that it allows researchers (and the general public) to test the claims of governments and schools using their own data.

Image is by John Guenther taken at Muludja Remote Community School

John Guenther is currently the Research Leader—Education and Training for Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, based in Darwin. His work focuses on learning contexts, theory and practice and policies as they connect with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Between 2011 and 2016 he led the Remote Education Systems project with the CRC for Remote Economic Participation. More detail about John’s work is available at remote education systems.

John will be presenting on 10 Years of My School. Are we any the wiser? Implications for remote First Nations education at the AARE 2019 Conference. #AARE2019

He will also be presenting on Supporting teachers with Professional Learning for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cross-curriculum priority: A case study of two schools at the AARE 2019 Conference. #AARE2019

And, with Andrew Lloyd, John will be presenting on Interschool Partnerships: A study into effective partnership practices between an interstate boarding school community and a very remote Aboriginal Community at the AARE 2019 Conference. #AARE2019

Hundreds of educational researchers are reporting on their latest educational research at the AARE 2019 Conference 2nd Dec to 5Th Dec. #AARE2019 Check out the full program here

John Guenther is currently the Research Leader—Education and Training for Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, based in Darwin. His work focuses on learning contexts, theory and practice and policies as they connect with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Between 2011 and 2016 he led the Remote Education Systems project with the CRC for Remote Economic Participation. More detail about John’s work is available at

John Guenther is currently the Research Leader—Education and Training for Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, based in Darwin. His work focuses on learning contexts, theory and practice and policies as they connect with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Between 2011 and 2016 he led the Remote Education Systems project with the CRC for Remote Economic Participation. More detail about John’s work is available at